He influenced the sound system world like no other. His dances resembled religious masses, which even non-believers describe as a spiritual experience. When Rasta-influenced reggae had to make way for very worldly dancehall, he was the lone caller in the desert who kept the roots flame burning with UK steppers. Jah Shaka was not driven by his ego, but by his self-imposed mission to make the world a better place. He died unexpectedly on 12 April 2023. Shaka follower and dance muff David Katz remembers some of his most intense sessions.

Text: David Katz /// Photos: David Corio

This article was first published in June 2023 (RIDDIM 03/2023).

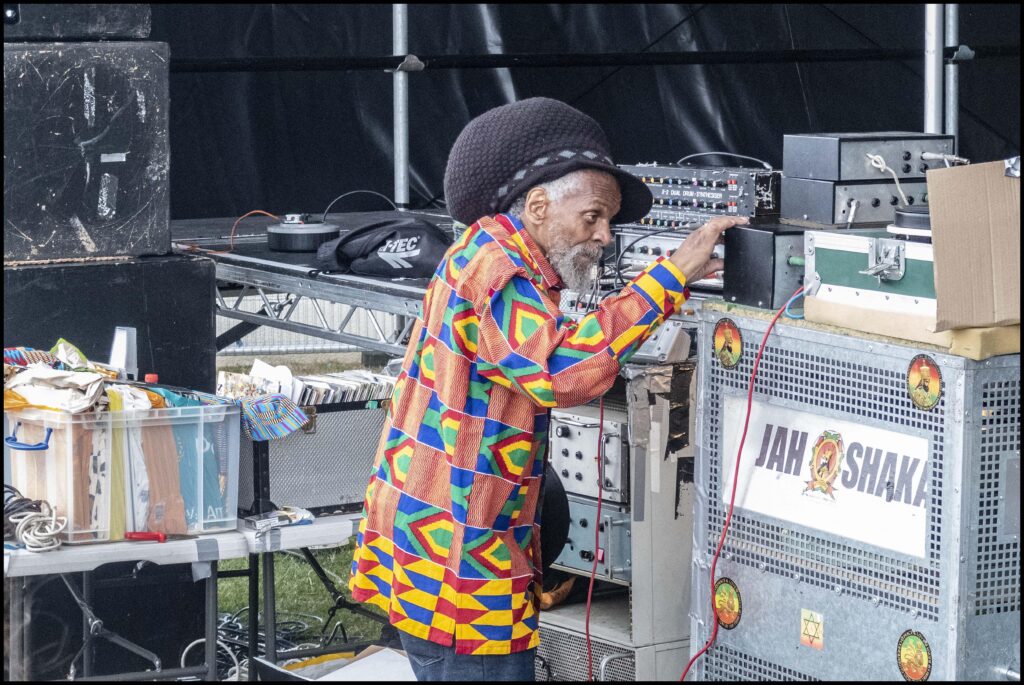

As I write these words, the reggae community is still reeling from the unexpected death of Jah Shaka, the towering giant of the British sound system scene who made such a dramatic impact across the globe. Through a career that lasted over 55 years, Jah Shaka singlehandedly transformed the sound system landscape with a distinctive and idiosyncratic playing style that proved highly influential, ignoring the dominant trends to focus exclusively on contemporary reggae that was politically relevant and spiritually uplifting, the music he played and the records he produced both serving as forms of inspiration and empowerment for the downtrodden and the oppressed. At the many dances he held in diverse underground spaces, playing in a trance-like state on one ancient and archaic Garrard turntable that was reportedly built in the late 1940s, Jah Shaka would chant messages of encouragement as well as exhortations of transcendent devotion to Rastafari over the microphone, drenching everything in delay and reverb, and adding custom-built effects and live percussive elements to increase the dramatic tension; through his masterful use of the preamp, along with a portable syndrum and a homemade siren box, he made his sessions visceral and immersive, boosting the subsonic bass frequencies at regular intervals to stimulate a transportive and transformative experience. Jah Shaka’s dances were never about mere entertainment, ego, or showmanship. Instead, the sessions were meant to uplift and inspire, to help his attendees free themselves of their mental shackles, to dance without restriction and to generally elevate oneself as part of a process of reaching a better place, both individually and collectively.

Emerging in Jamaica in the years following World War II, the sound system has since become a complex art form, in which several different elements must coalesce for any given set to make an impact. To ensure drawing power unmatched by rivals, exclusive material has always been key; stylistic microphone chanters have been part of the picture since the early 1950s and although sheer wattage can act as a magnet, especially in Jamaica’s open-air terrain, the massive banks of amplifiers and speaker boxes also need to be managed with skilled finesse. Arriving in the UK in the early 1950s through the ”Windrush Generation” immigrants that brought the practice with them, sound system culture enjoyed a particular evolution in Britain and the preamp has been a key part of the experience; this crucial bit of kit allows frequencies to be boosted or cut at will and directed spatially through different speakers, giving dub sound systems like Jah Shaka an importance difference to their Jamaican counterparts. Above all, each sound system must have a distinctive identity that sets it apart from competitors and Jah Shaka’s sound system had that distinctiveness in a surprising number of ways.

Although I attended my first Shaka dance over 35 years ago, I remember it like it was yesterday: upon entering the pitch-black space under a south London railway arch, the atmosphere hit me like a mallet; heavily permeated with ganja smoke, a mass of sweaty bodies stood expectantly before an impressive array of hand-made wooden speaker boxes, as the opening strains of Yami Bolo’s ”Jah Made Them All” raked the air, Shaka’s manipulation of the preamp initially aimed slices of treble notes at our headspaces. The massive hangar was laden with expectation, though of what was not yet entirely clear, and although the song was instantly recognizable, it sounded nothing like the actual record because of the way that everything had been re-balanced, skewed entirely in the treble spectrum; guitar and keyboards were jagged bursts that hit our brows, along with Yami’s distinctive vocals, but the rhythmic foundation was but a ghostly echo that barely registered. Then, without warning, the short man with the massive bulbous tam that stood by a sole record deck gave a mighty flick of his wrist to overwhelm our senses by completely flipping the orientation, so that the bass notes rattled our ribcages and battered our waists. As the thunderous bass, electronic drums, and Shaka’s syndrum accompaniment worked their way down the length of our spines, spurring our legs into action, attendees cried out in ecstasy as they danced with reckless abandon. With his eyes tightly shut and a microphone in hand, his body swaying gently to the rhythm, Shaka began to chant praises to Jah, seemingly in another realm.

As the night wore on, a series of incredible tunes made their way onto the platter and into our consciousnesses: there were exclusive, previously unheard dub-plate mixes of old favorites such as the Wailing Souls’ ”Very Well” and Cultural Roots’ ”Mr Boss Man”, as well as Creole’s ”Beware” and its ”Kunta Kinte” dub counterpart, while at other moments, freshly recorded works by upcoming British artists were also aired. I recall that there were songs then ruling the reggae charts, such as Junior Delgado’s dancehall styled ”Raggamuffin Year”, the title track of a then-current album produced by Augustus Pablo, but those songs were presented in a unique manner, thanks to Jah Shaka’s masterful control of equalization, the sound being stretched along the entire audio spectrum, and further enhanced by the dramatic applications of reverb and delay, the way that the speaker stacks were constructed affecting the spatial placement as Shaka worked his wonders with the preamp. As the night wore on, sonic revelations abounded in quick succession, and, for the second time in my life, I found myself compelled to dance, my body rocking and popping along with everyone else until long after daylight broke. The overriding feeling was witnessing something of great gravitas, but with rapturous, abundant joy more than anything else. Such was my introduction to the extraordinary phenomenon of Jah Shaka’s sound system, of which I became a devoted follower from then onwards.

At the many dances he held in diverse underground spaces, playing in a trance-like state on one ancient and archaic Garrard turntable that was reportedly built in the late 1940s, Jah Shaka would chant messages of encouragement as well as exhortations of transcendent devotion to Rastafari over the microphone.

An intensely private person who revealed little personal information during his lifetime, Jah Shaka spent his formative years in rural Clarendon, south Jamaica, before his parents moved the family to the UK in 1956 in search of betterment; they settled in southeast London when he was five years old, and it was as a teenager in 1968, while attending Samuel Pepys Comprehensive School at Sprules Road in Brockley, that Jah Shaka started playing in a band and began an apprenticeship on local soul sound system Freddie Cloudburst, which mostly played American soul music; he got his start as a ”box boy” who would help to transport and set up the speaker boxes, later ensuring that the amplifiers and speakers were functioning properly, and finally becoming the resident selector, but after being inspired by black activists such as the Jamaican hero of self-determination, Marcus Garvey, and African American freedom fighters like Malcolm X and Angela Davis, by 1970 he had formed his own sound system, which he named Jah Shaka after the Zulu warrior who tried to keep the British out of his kingdom in southern Africa in the late 1800s. Armed with exclusive dubplates from the most important record producers in Jamaican and the UK, including Lee ”Scratch” Perry, Bunny Lee, Joe Gibbs, Yabby You, the Abyssinians, the Twinkle Brothers, Al Campbell, and others, and with a powerfully commanding presence on the microphone, Jah Shaka soon began making an impact on the sound system underground, triumphing at many a sound clash, including against more established rivals, but along with the accolades came tensions with the police, who infamously raided a Jah Shaka dance held at Malpas Road in Brockley in April 1975, beating attendees, and causing hundreds of pounds worth of damage to his equipment. In fact, Jah Shaka’s southeast London base was then a flashpoint of hostile race relations, with neo-Nazis and other white fascists firebombing the Moonshot youth club in 1977 and the Albany Empire in 1978.

The overriding feeling was witnessing something of great gravitas, but with rapturous, abundant joy more than anything else. Such was my introduction to the extraordinary phenomenon of Jah Shaka’s sound system, of which I became a devoted follower from then onwards.

Against this antagonistic backdrop, Jah Shaka simply redoubted his efforts to embrace his work and to continue to engage with his community. He subsequently established a residency at Phebes Nightclub in Hackney during the late 1970s, followed by another at Club Noreik in Tottenham, and was then crowned the top sound system in Britain at the Black Echoes Reggae Awards in 1980 and 81. He cultivated close friendships with key reggae artists, including fellow Clarendonians too, such as Freddie McGregor, Barrington Levy and Style Scott of the Roots Radics. Although his audience was almost entirely black in these heady years, during the late 1970s, Jah Shaka’s sonic wizardry made a dramatic impact on the post-punk music of Public Image Limited and the Slits, whose members had been introduced to his dances by Don Letts, and a wider audience was hipped to his importance when he was captured in action in Franco Rosso’s evocative 1980 urban drama ”Babylon”, playing himself at a south London sound clash as the film’s action draws to its climax.

Jamaican reggae subsequently underwent dramatic changes during the mid-1980s as the dancehall style came to the fore, its output largely preoccupied with lasciviousness, violence, and frivolity, and music with a Rastafari focus became passé; British sound systems inevitably embraced the new style, but unlike his competitors, Jah Shaka opted to become the lone voice in the wilderness that kept the roots reggae flame burning. When slackness and gun talk was the rage, Shaka was the voice of reason, a committed individual who only played music with an overriding message of spiritual or social importance, advancing an up-tempo homegrown variant of reggae that became known as ”UK Steppers”, his early productions in this style given kudos when championed by the noted BBC radio disc jockey, John Peel. With a backing band he dubbed the Fasimbas after a local activist group established in response to the discriminatory treatment of black children in the British school system, from 1980 Jah Shaka produced original music with upcoming unknowns such as African Princess, Sister Audrey, and former Capital Letters frontman, Junior Brown, as well as self-produced favorites such as ”Revelation 18” and ”Lion Youth.” Later, he would produce likeable releases with iconic reggae vocalists such as Bim Sherman, Johnny Clarke, the Twinkle Brothers, Max Romeo, and Horace Andy, among others. He also released an impressive series of dub albums, including collaborative works with Aswad and Mad Professor, sharing premises with the latter in the early 1980s in Peckham; in the same era, he also ran a community hub known as the ”Culture Shop” in New Cross, which had a record store, Caribbean food outlet and Rastafari-oriented hair salon, the space acting as a focal point for local black youth. Although his record productions did not achieve much in the way of mainstream success, they were consistently popular with his core audience of reggae and dub devotees; more importantly, the uniqueness of his sound system would ultimately inspire noteworthy acolytes such as Iration Steppas in Leeds, the Zion Train collective which began in London and later decamped to Cologne, as well as the Disciples, a pair of white English brothers from southwest London who were among the first non-black practitioners to try their hand at dub. Later, the Moa Anbessa sound system of Italy, France’s OBF and countless other sound systems throughout the UK and Europe acknowledged their great debt to Jah Shaka, as well as other practitioners in Japan, Mexico, Brazil, and elsewhere.

During the 1990s, Jah Shaka’s residency at the Rocket, adjoining North London Polytechnic, significantly broadened his audience. I remember very clearly that far more white people began to attend the sessions then, which had an accompanying slideshow operated by Pax Nindi, former frontman of the group Harare Dread. The proximity to the Poly meant that students were in abundance, and there was a growing audience of young Europeans too. The Rocket residency began a long process of growth for the sound system, and a shift in the nature of London events, since prior to that point, Shaka would tailor his selection based on the venue he was playing at, and the sound would always be set up in such a way as to match the space, meaning that no two sessions were ever exactly identical, even though there was the continuity of the Rastafari focus, and the manner in which he played the sound. In any case, the wider audience gradually resulted in an unprecedented touring schedule that would see Jah Shaka bring his musical experience all over Europe and on to Africa, Japan, Mexico, Peru, and other territories.

As the dancehall style came to the fore, its output largely preoccupied with lasciviousness, violence, and frivolity, Jah Shaka opted to become the lone voice in the wilderness that kept the roots reggae flame burning.

At the same time, Jah Shaka continued to progress as an activist and enabler as his own personal journey continued to unfold: after travelling to Africa in 1984 and 1990, he established the Jah Shaka Foundation in Accra in 1992 to distribute medical supplies, library books and other materials to schools and medical clinics, and there were charitable works in Jamaica, Ethiopia and Kenya too. It all pointed to the lack of ego and the continued involvement with projects that mattered, rather than chasing fame and empty glory. He remained resolutely steadfast in his principles, travelling for extended periods in Africa, walking the walk when so many others merely talked the talk. Shaka’s playlists always spoke of the need for human unity and pointed to the greatness of African civilizations, forming the backdrop for his fervent chants about the powers of the Almighty and the need for positive actions from Mankind, and here he was demonstrating that he meant what he said, that his proclamations were heartfelt, and not the result of mere sloganeering or posturing.

At the now-defunct Tropical Isles club, Shaka played all the way until 10am or thereabouts, with sunlight bathing the place for the last phase. The sessions lasted some 14+ hours at least, and Shaka himself never took a break. The man was clearly on a mission and the music was obviously a form of sustenance.

As his fame grew and he increasingly became a festival headliner, he continued to command large audiences at the events he regularly held, both in the UK and abroad. And so many of these events remained exceptional. I remember with fondness his appearance at the 2007 edition of Rototom Sunsplash in Osoppo, northeast Italy, when he played a set of entirely unknown music that stretched through the night and went until far after sunrise; sharing the experience with RIDDIM’s Ellen Köhlings and Pete Lilly, we were all transfixed for the entire time as Shaka threw new musical mysteries at us, rendering a very special feeling in the air. Shaka mentored the son who became known as Young Warrior after launching his own sound system in 2011, and another session I will never forget was that delivered by the pair of them at the WOMAD festival in 2016, another joyous occasion filled with spiritually uplifting sounds, much of which was unknown to me and delivered as only Shaka could, even if the set was shorter than usual. Other highlights that have stayed with me include the Dub School sound clash he played against Fatman on Fatman’s north London home turf in 1991; although Fatman had U Brown and various other toasters, and Shaka was all alone as usual, whatever dub plate Fatman drew for, Shaka drew a better one and never let up the entire night, crowning Shaka the winner by far. There was also a night of exceptional energy at the now-defunct Tropical Isles club, under the Bow flyover in east London, where Shaka played all the way until 10am or thereabouts, with sunlight bathing the place for the last phase, the sessions lasting some 14+ hours at least, and Shaka himself never taking a break. How he managed such efforts week after week for so many decades is beyond me, though the man was clearly on a mission and the music was obviously a form of sustenance.

A Jah Shaka session really was akin to a religious experience; even those who claim not to be religious themselves will often report feeling something spiritual after witnessing the proceedings. And although his core audience was black for the first decades of his career, Shaka never closed his sessions to anyone; indeed, the event flyers typically stated, ”How good and pleasant it is to see all nations come and hear Jah music.”

Jah Shaka was the patriarch of a large family that now includes several children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren. The Nine Night that was held in his honor on 21 April 2023 at the Great Hall of Goldsmiths, University of London, was a beautiful outpouring of love that was estimated to have been attended by over 1,000 people, with many turned away due to health and safety concerns. Although we are unlikely to encounter one such as him again, his lasting legacy of recorded music and sound system activity ensures that his work lives on. All hail Jah Shaka, the mighty Zulu Warrior, one of the greatest sound system champions of all time!