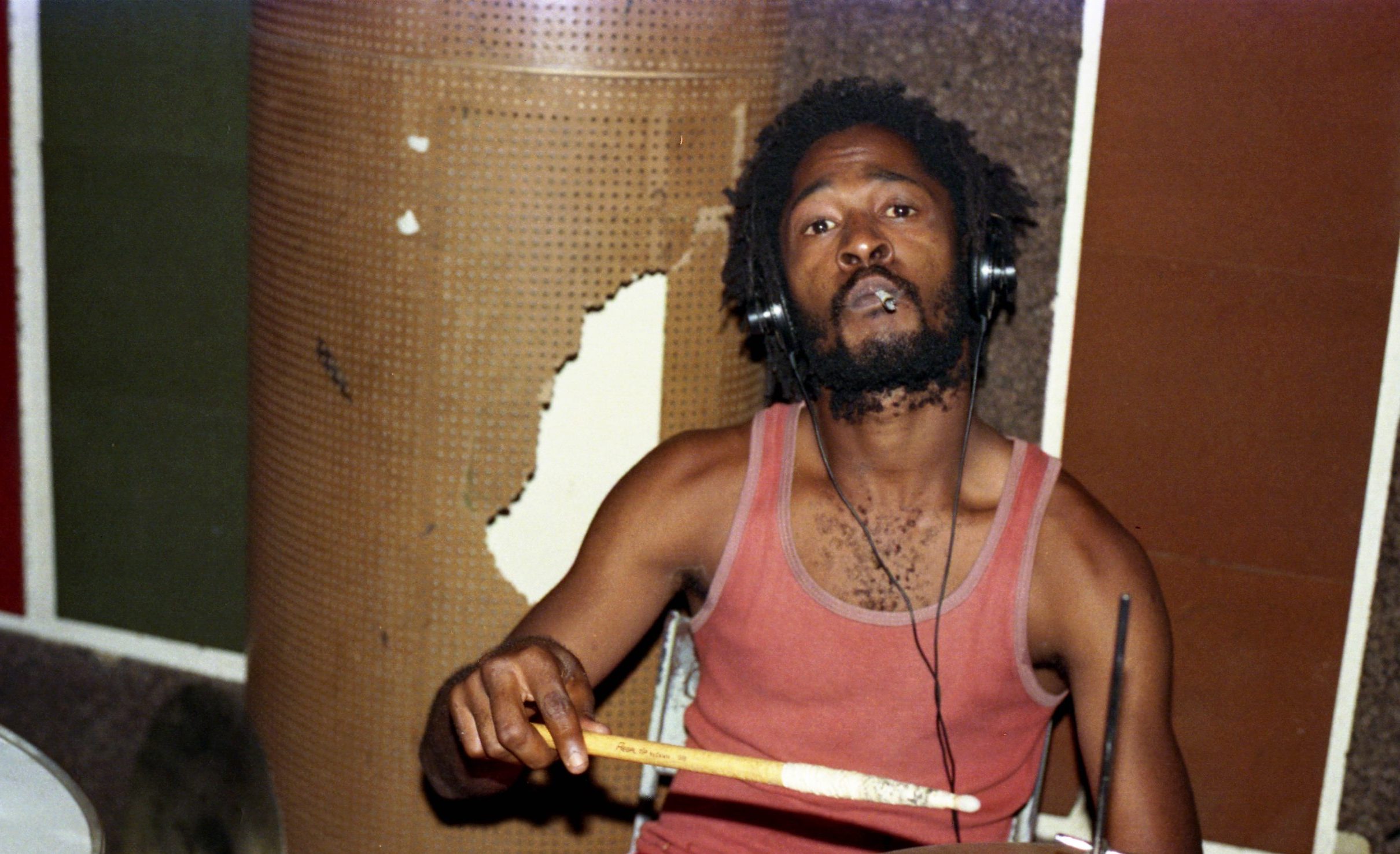

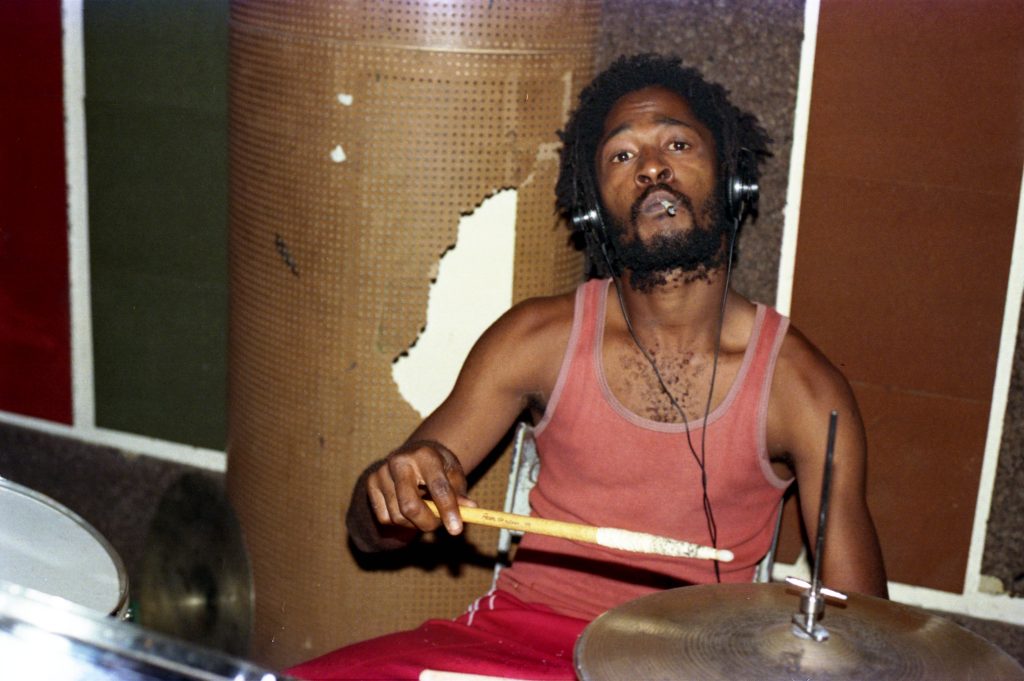

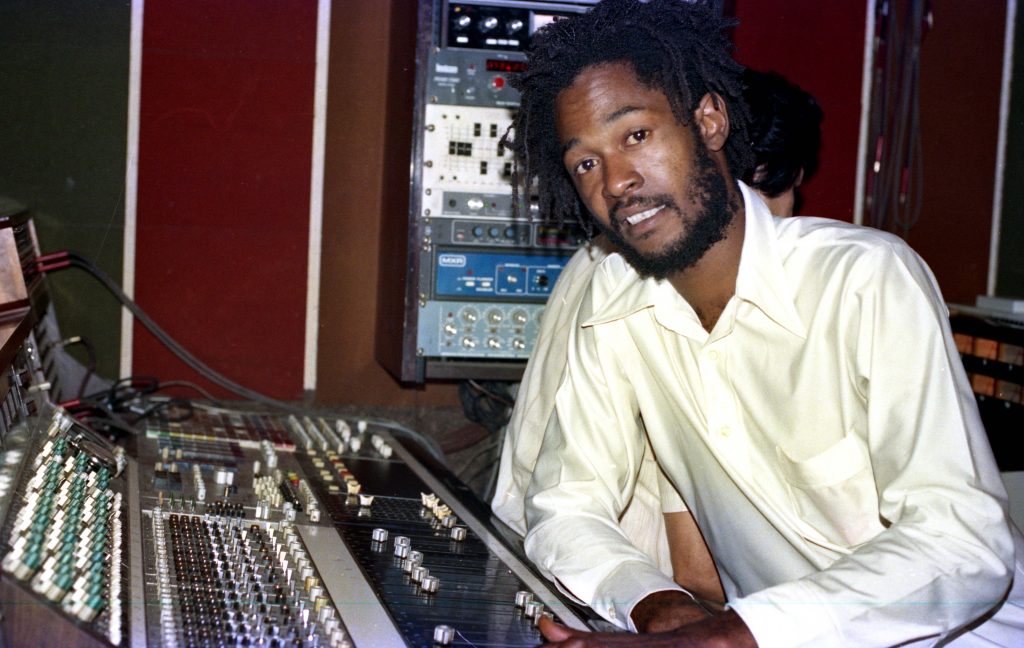

He wore several different hats during his long career, having been active as a toaster, a percussionist, a drummer, and most notably an audio engineer. Another of the unsung heroes of reggae, he was key to the establishment of the Channel One sound that ruled Jamaica during the mid-1970s but remained a behind-the-scenes figure, so much so that his death in August (2025) at the age of sixty-five went largely unreported. Reggae connoisseurs are well aware of his importance and those fortunate to work with him remember a dedicated individual with an intuitive feel for mixing and a forceful drumming style, his understated sense of humour easing the atmosphere of many a recording session. David Katz remembers Barnabas.

Text: David Katz /// Photos: Beth Lesser

The youngest of three children, he was born Stanley Bryan in 1960 and raised at Sunlight Street, a backroad on the border of Whitfield Town and Rose Town in western Kingston. ”I was raised by my mother and she was an independent worker,” said Barnabas. ”She used to do sewing, sell clothes and all those things.”

His mother taught him proper manners and respect, which would stand him in good stead in this flashpoint community, where partisan violence between followers of the leftist People’s National Party and the right-wing Jamaica Labour Party had been an issue since the mid-1940s. Growing up in a disenfranchised single-parent household had its challenges, but young Stanley maintained a positive outlook and a cheeky sense of humour, his nickname stemming from the vampire Barnabas Collins in the television drama, ”Dark Shadows,” reportedly because he stuck his teeth out to impress the girls in school.

Everything changed one fortuitous day in 1973 when Barnabas was on his way to the shops on an errand for his mother; a neighbour asked him to fetch Joseph Hoo Kim for her, because the jukebox in the bar she ran had broken down. The Hoo Kims were prominent entrepreneurs in the area, having started out with an ice cream parlour, rum bar and liquor wholesale at the junction of Maxfield Avenue and Spanish Town Road; more recently, they had acquired larger premises at 29 Maxfield Avenue, just a few blocks away from Barnabas’ home. The young lad thus found himself in the studio for the very first time, waiting for a technician who could fix the jukebox as Boris Gardiner was in the midst of recording ”Every Nigger Is A Star,” and when Joseph Hoo Kim sent him to the shops to fetch him a soda, Barnabas made sure to give the man back his change, sowing the seeds of a longstanding working relationship.

Barnabas’ mother eventually bought a house on Raphael Street, which was just opposite the studio itself, so Barnabas began frequenting the place: ”I used to pass the studio going to Whitfield Town School, then I start going to the studio.”

He soon began helping informally with the jukebox deliveries, which brought him onto the Channel One sound system and ultimately into the studio full-time. As Barnabas explained, ”I used to be on the sound system first as a deejay, and then I start going to the studio and learn about engineering, then I start learning to play the drums by watching Sly Dunbar.”

Spontaneity was the order of the day then and being at the right place at the right time had tangible results. For instance, ”Sister Fay,” his debut recording, was voiced for producer Roy Francis over the Chantells’ ”Effort In Yourself,” because, as Barnabas recalled, ”I was at the studio and he just asked me to do something on it.”

More importantly, Barnabas settled into an engineering role after a period of closely observing Joseph’s brother Ernest at the mixing desk: ”Ernest Hoo Kim, that’s my teacher. He used to harass the board and mix the thing alone until I learned to do it just like how he does it. One of the first ones I did is with Earth And Stone, ”In Time To Come,” and when I was there Ernest balanced the mixing board, so all I had to do was mix the instruments. I didn’t know how to balance it as yet, and then I started learning to do it more and more.”

Barnabas played percussion on Dillinger’s ”Bionic Dread,” Cornel Campbell’s ”Stalowatt,” Leroy Smart’s ”Ballistic Affair,” the Mighty Diamonds’ ”Stand Up To Your Judgement” and Winston Jarrett’s ”Man of the Ghetto” and after observing Sly Dunbar at work began playing drums on Barbara Jones’ recordings for producer Alvin Ranglin. He voiced a handful of deejay tracks for Ranglin too and there were one-offs for Yabby You, Dennis ”Struggle” Hamilton and Ty Hutchinson, but engineering and drumming became Barnabas’ main preoccupations.

”I mixed mostly the deejays like Ranking Trevor, Dillinger, Trinity, Clint Eastwood, and I used to do some dubs too, use the delay and put the reverb on the drums,” said Barnabas. ”I used to mix dubs for Phil Pratt, cos he liked how I work, and I did some dubs for Al Campbell too.”

Barnabas’ dubs have a sound system orientation, with plenty of delay and added emphasis on the drums. In addition to helping with the ”Revival Dub” and ”Satta Dub” LPs and the ”Super Dub Disco” set for Bunny Lee, Barnabas mixed the delicious dub to Linval Thompson’s ”Six Babylon”; ”The Cold Crusher,” produced by Phil Pratt, was released in limited quantities in New York on the Express label in 1978, and the same tracks were issued in the UK by Burning Sounds as ”Star Wars Dub,” but in a different order and with alternate mixes. Barnabas mixed ”Top Ranking Dub” for former south London sound man Charles Reid and was the main mixer on ”King’s Dub,” released in Jamaica by Dudley ”JA Man” Swaby in 1980; he is credited as the engineer on four tracks on ”Three The Hard Way,” released by Silver Camel in the UK in 1981, and he gets a partial credit on Zola and Zola’s ”Universal Dub” too.

Barnabas said that, some time after Channel One upgraded to sixteen tracks in 1979, King Tubby wanted to hire him to work at Tubby’s studio in Waterhouse, such was his renown as a dub mixer. ”King Tubby wanted to take me there because Tubby liked how I mix the dubs, and Bunny Lee told him he could get me to come along but I decide I wasn’t leaving Channel One, because King Tubby’s was only a four-track studio and Channel One was sixteen tracks.”

Away from the dub scene, Barnabas’ outstanding moments at the mixing desk include the twelve-inch edition of the Wailing Souls’ ”Kingdom Rise Kingdom Fall,” Barry Brown’s ”I’m Not So Lucky,” Michael Prophet’s self-titled second LP, the Itals’ ”Brutal Out Deh” and Eek-A-Mouse’s ”Wa Do Dem,” as well as early work for Barrington Levy and Cocoa Tea, plus Augustus Pablo’s ”Earth Rightful Ruler.” And when Ernest Hoo Kim backed away from the music scene, Barnabas became the mainstay at Channel One. ”After Ernest retired I was doing most of the works. He had so much work in other fields and was a technician more than in the studio, because he was very busy fixing machines and all of that. So he recommend most of the customers to work with me.”

Barnabas also worked as a mastering engineer at Channel One. ”The mastering engineers, they used to EQ the console and they never used to do it so well. So Joe-Joe asked me to go and make sure that they was doing it flat, straight from the tape. So I did that on all of Channel One’s productions, all the way through.”

Barnabas became a member of the Gladiators’ backing band in 1980 and toured with them internationally to 1983. ”It was a great experience. I remember being in America one time with them but I used to tour mostly Europe with them. We did some good concerts at the 100 Club in London, we had a mixed audience there.”

During the mid-1980s, Barnabas was also moonlighting at studios such as Aquarius and Dynamic Sounds, playing drums on works by Tenor Saw and other artists in the foundation dancehall phase. However, western Kingston was becoming more violent. The Hoo Kims were thus planning to move Channel One to new premises in the safer confines of West King’s House Road, but the move somehow never happened. With Maxfield Avenue in a downward spiral of wanton violence and urban decay, Barnabas relocated to Los Angeles in 1988 to work at I and I Sound Studios, moving on to work as a dub engineer at Sir Tommy’s Studio in Flatbush in 1990.

After a decade in New York, Barnabas returned to Jamaica where he continued to drum for leading reggae performers, including Sugar Minott, the Ethiopians and Max Romeo, but was less active in recent years as health issues took their toll. Walk good, Stanley ”Barnabas” Bryan, and thank you for your varied contributions to the evolution of Jamaican popular music.